Words: Fanny J. Crosby, 1874

Music: Silas J. Vail, 1874

Fanny Crosby probably was the most prolific hymn writer who ever lived, with approximately 9,000 texts (surpassing even the 6,000 or so of Charles Wesley). And though only a fraction of these have stood the test of time, even a small fraction of 9,000 leaves an impressive number of hymns that still give voice to our praises and comfort to our souls. She was truly the standout writer of the early phase of gospel music, and of the 19th century American hymn writers generally; Wilhoff's article in the Encyclopedia of American Gospel Music notes that "with the possible exception of Isaac Watts and Charles Wesley, Crosby has generally been represented by the largest number of hymns of any writer of the twentieth century in nonliturgical hymnals."(92)

Crosby's tremendous success as a hymn writer (in fame if not in fortune), recognition as a champion of social causes, and reputation for generosity and good works fostered an idealized view of her life that fit the mold of the optimistic, romanticized views of the era. She was portrayed as an unfailingly cheerful "Protestant saint," overcoming all obstacles through hard work and simple faith. A recent biographer, Edith Blumhofer, expressed frustration with journalistic conventions of the era (so different from today!) that seemed purposely to avoid addressing areas of her life that were far less than idyllic.(xii)

Truth be told, Fanny Crosby was in difficult straits in 1874, when "Close to Thee" was written. Her husband, Alexander Van Alstyne, made a meager living as a church organist and private teacher, and Fanny's own income--despite the huge contribution she made to gospel music--was relatively small. When they had money, they had the habit of giving much of it away to those who were worse off; consequently, they lived month to month and moved frequently from one apartment to another. Sometimes they stayed at different addresses.

There was an increasing strain within their marriage that led to a permanent separation just a few years later. No doubt money was a great deal of it; perhaps it was also difficult for Alexander to accept Fanny's celebrity, when his own musical efforts were largely unsuccessful. But another factor, no doubt, was the lingering anguish caused by the crib death of the couple's only child in 1859. After moving to New York in the early 1860s, Fanny and Alexander never spoke of the child; only late in life did Fanny reveal this tragedy, to the shock of her closest friends.("Crosby," Wikipedia)

The sensibilities of the era tended to consider this troubled side of Crosby's life off limits for discussion, and it may ultimately have been to the detriment of her later critical reception. The great American hymnologist Henry Wilder Foote, for example, might not have been so quick to dismiss Crosby's poetry as "overwrought sentimentality" had he known the real depth of personal suffering from which she spoke.(Foote, 270) Her lyrics gain an added dimension of meaning when we look at them as the writings, not of a stereotyped "cheerful blind girl," but of a real woman who had misfortunes and disappointments, made mistakes, and got through the best she could by clinging to a simple faith and an ethic of service.

"Close to Thee" was just such an autobiographical outburst. Crosby said of this hymn,

Towards the close of a day in the year 1874 I was sitting in my room thinking of the nearness of God through Christ as the constant companion of my pilgrim journey, when my heart burst out with the words:But this reveals another problem in unraveling Fanny Crosby's lyrics--this is from a volume of anecdotal material, taken from interview with Crosby many years after the incident described. Ira Sankey related a different story of the hymn's origin:

Thou, my everlasting Portion,

More than friend or life to Thee;[sic]

All along my pilgrim journey,

Saviour, let me walk with Thee.

(Crosby's Story, 79)

The late Silas J. Vail having composed this tune brought it to Fanny Crosby and requested her to write words for it. As he was playing it for her on the piano, she said, "That refrain says, 'Close to Thee, Close to Thee.' Mr. Vail agreed that that was true, and it was agreed that it should be a hymn entitled "Close to Thee."(Sankey, 362)It is possible that both accounts are true, as far as they go; Crosby's account of the origin of the first stanza does not include the refrain, and Sankey's account of Vail's encounter mentions only the refrain and not the stanzas. Perhaps Vail, editor of the hymnal in which "Close to Thee" first appeared, matched the stanzas to the germ idea of the refrain he had discussed with Crosby. Vail did something similar when he added a chorus to Frederick Faber's "There's a wideness in God's mercy." (Usually under the title, "There's a fullness in God's mercy," this was one of Vail's most popular hymns.) "Close to Thee" was first published in 1874, in Songs of Grace and Glory (New York: Horace Waters & Son), edited by William F. Sherwan and Silas J. Vail.

Stanza 1:

Thou my everlasting portion,

More than friend or life to me;

All along my pilgrim journey,

Savior, let me walk with Thee.

The opening line of this stanza is rooted in the language of Old Testament poetry. A "portion" in the legal sense of an allotted inheritance came to signify the circumstances of life in general; or, as we still say in English, our "lot in life." The priests of Israel had God alone as their "portion" both literally and figuratively, as God told Aaron from the time of the Exodus: "You shall have no inheritance in their land, neither shall you have any portion among them. I am your portion and your inheritance among the people of Israel."(Numbers 18:20) In an era when the worth of a man, a family, or a tribe was tied up in land and possessions (is it any different now?), the sons of Aaron had to look beyond the physical to the spiritual.

David adopted this language to himself in the Psalms: "The LORD is my chosen portion and my cup; You hold my lot."(Psalm 16:5) "I cry to you, O LORD; I say, 'You are my refuge, my portion in the land of the living.'"(Psalm 142:5) This is continued by other poets: "My flesh and my heart may fail, but God is the strength of my heart and my portion forever."(Psalm 73:26) "The LORD is my portion; I promise to keep Your words."(Psalm 119:57) The everlasting nature of God's faithfulness is emphasized, and also our choice to receive our inheritance in Him through our obedience to Him.

Perhaps the most moving instance of this poetic image, however, is from Jeremiah's Lamentations:

He has filled me with bitterness;Sometimes it takes losing everything else to make us realize that our real hope and future, our "everlasting portion," is in the Lord. Was this the passage that sparked Crosby's lines? She had endured many things in her life that could have made her bitter, but like the prophet, clung to the one thing that made sense of life, and could not be taken away.

He has sated me with wormwood.

He has made my teeth grind on gravel,

and made me cower in ashes;

my soul is bereft of peace,

I have forgotten what happiness is, so I say,

"My endurance has perished;

so has my hope from the LORD."

Remember my affliction and my wanderings,

the wormwood and the gall!

My soul continually remembers it

and is bowed down within me.

But this I call to mind,

and therefore I have hope:

The steadfast love of the LORD never ceases;

His mercies never come to an end;

They are new every morning;

great is Your faithfulness!

"The LORD is my portion," says my soul,

"therefore I will hope in Him."

(Lamentations 3:15-24)

Refrain:

Close to Thee, close to Thee,

Close to Thee, close to Thee!

All along my pilgrim journey,

Savior, let me walk with Thee.

"Walking with Jesus" and being "close to Jesus" are major themes of Crosby's hymns, and reflect the 19th-century Evangelical presentation of Jesus as a warm, welcoming Friend.(Blumhofer, 253ff.) The Victorian sentiment in religious poetry tended toward emotionalism, and if it sometimes went to excess, it is not any more to our credit today that we are often uncomfortable expressing such emotion. Even men of the "repressed" Victorian era seemed to find much less difficulty in expressing affection toward a male friend, not to mention toward our Savior!

There is a natural tendency when walking with a friend to fall in alongside them; we would hardly call it "walking with" someone if we did not. We walk close enough to converse, to see the person's face; in other words, to be in intimate communication with each other. If it is a close family member we will walk a little closer because we are at ease with them, and little children very naturally take the hand of someone they trust to keep them safe.

The letters of John are full of references to the Christian's walk, centering on the key passage, "Walk in the light, as He is in the light."(1 John 1:6) We do this when we "walk in the same way in which He walked,"(1 John 2:6) "according to His commandments,"(2 John 1:6) "walking in the truth."(3 John 1:3) A walk, of course, is made up of steps; every step we take, in every decision we make, is either closer to Jesus or further away. If we learn to know Him better, our love for Him will increase; and if our love increases, our desire to walk close to Him, in constant communion with Him, will keep our steps in the light with Him.

Stanza 2:

Not for ease or worldly pleasure,

Not for fame my prayer shall be:

Gladly will I toil and suffer,

Only let me walk with Thee.

Refrain:

Close to Thee, close to Thee,

Close to Thee, close to Thee!

Gladly will I toil and suffer,

Only let me walk with Thee.

This was an honest statement in view of Fanny Crosby's life. The 1870 U.S. Census shows that she and her husband were then living in a boarding house in the middle of Manhattan's 8th Ward. Today, this is the exclusive SoHo district, but back then it was a poor working-class neighborhood just a few blocks from the red-light district off Broadway. By contrast, Crosby's friend Phoebe Knapp Palmer (composer of "Blessed assurance") lived in an urban mansion in the Williamsburg neighborhood of Brooklyn, then a prestigious enclave of wealthy industrialists.

Despite their difficult financial circumstances, Fanny seemed always to keep in mind that others were more in need. When the couple gave lecture-recitals to raise money, they routinely donated half the proceedings to the poor. Beginning in the late 1860s, Fanny worked with rescue missions in some of the toughest New York neighborhoods, speaking and counseling whenever she could. And when friends took it upon themselves to organize activities to raise funds for Crosby in her elderly years, her reaction was always to insist that she was not in need.("Crosby," Wikipedia)

James 4:3 says, "You ask and do not receive, because you ask amiss, that you may spend it on your pleasures." Fanny Crosby received that for which she asked, because the example of her life shows that she wanted most to be a help and comfort to other people. Her songs continue to do this even today. To take an example from the Bible, the apostle Paul showed that his great desire and constant prayer was for the furthering of the gospel of Christ. In the first chapter of Philippians, he related the circumstances of his imprisonment and the opposition he received even from some in the church. There were selfish brethren who thought to eclipse his work while Paul was unable to operate freely. But his conclusion tells us all we need to know about Paul: "Christ is proclaimed, and in that I rejoice."(Philippians 1:18)

What do we seek in our prayers? The model prayer that Jesus gave His disciples mentions material things only in passing--our "daily bread." These things are important and necessary, but they are not the most important and necessary; the emphasis by far is on seeking a right relationship with God and doing His will. We know how to pray for a material blessing, and for deliverance from a physical hardship. When we learn to pray just as earnestly that we may be better servants to others, better proclaimers of the gospel, and better examples of holy living, we will be more pleasing to our Father.

Stanza 3:

Lead me through the vale of shadows,

Bear me o'er life's fitful sea;

Then the gate of life eternal

May I enter, Lord, with Thee.

Refrain:

Close to Thee, close to Thee,

Close to Thee, close to Thee!

Then the gate of life eternal

May I enter, Lord, with Thee.

The final stanza of this hymn uses two familiar old metaphors for the struggles of life--the "vale of shadows" and the "fitful sea." A search of 19th-century works in Google Books shows that these phrases were rather common in religious prose and poetry of Crosby's era. The "vale of shadows" is of course inspired by the "valley of the shadow of death" in the 23rd Psalm. The "fitful sea" was a stock poetic image, especially in the Anglo-American culture that so depended on sea travel. But in the context of a hymn, of course, it calls up the events of the Sea of Galilee when frightened disciples looked to their Lord to save them from a storm.

These phrases are commonplace, even cliched, for a good reason: they express the common experience of humanity. "Man that is born of a woman is of few days, and full of trouble,"(Job 14:1) and even to the most fortunate of lives "the years draw near of which you will say, 'I have no pleasure in them.'"(Ecclesiastes 12:1) Much of life really is spent in that valley, as we walk among dangers both physical and spiritual. Life really is much like a stormy ocean, as we are buffeted by pressures from many directions, ever changing, and threatening to overturn us.

Both images reflect the fact that we have to face events beyond our control, and sometimes completely unforeseen. But the child of God knows that we are not alone in this journey; instead, we can say with David, "I will fear no evil, for Thou art with me." On the ocean of life, we can remember with the Psalmist, "You rule the raging of the sea; when its waves rise, You still them."(Psalm 89:9)

About the music:

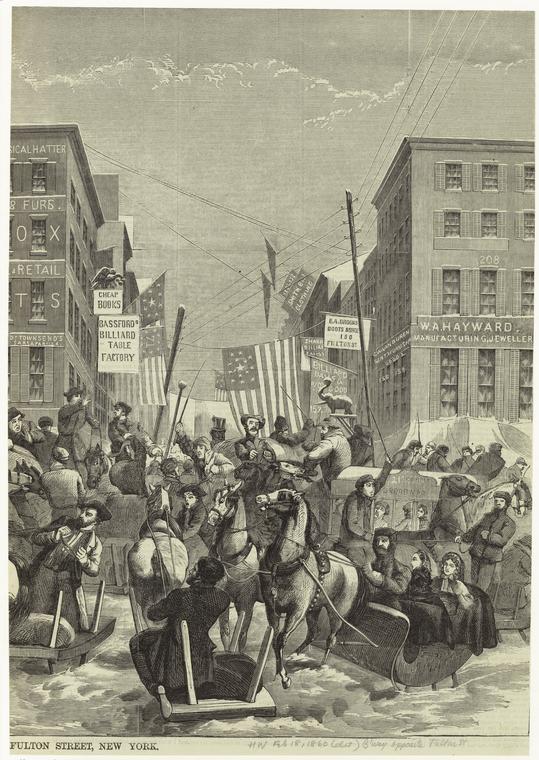

Silas Jones Vail (1818-1884) was one of the many lesser lights in the gospel music boom of the post-Civil War era, and like many church musicians before and since, he practiced a trade in order to pursue his passion. In the U.S. Census records from 1850-1870, his occupation is listed as "hatter," and Troy's New York City Directory from 1865 lists "Silas J. Vail, hats," in business at 118 Fulton Street.(894) This is in lower Manhattan, just a few blocks from the site of the World Trade Center; in Vail's day, it was a mercantile district between City Hall and the Stock Exchange. The hectic bustle of the growing super-city is seen in the print below, which shows hatters' and clothiers' shops along Fulton St. at the intersection with Broadway. Vail's shop was just another couple of blocks up Fulton.

Music was Vail's avocation for many years; a search of Worldcat.org, the list of works at Cyberhymnal, and Hymnary.org shows that Vail was writing music as early as 1858, and was active until at least 1876. These are the works discovered in the search, giving an idea of the extent of his activity:

- "Nothing but leaves" published in Christian Observer (New York), 1858

- "Beautiful Zion," quartet (New York: Horace Waters, 1859)

- Contributions to Shining Star: A New Collection of Hymns and Tunes for Sunday Schools (New York: Huntington, 1863)

- Editor, The Athenaeum Collection (New York: Horace Waters, 1863)

- "I will be true to the Stars and Stripes," quartet (New York: Horace Waters, 1864)

- Editor, The Diadem: A Collection of Tunes and Hymns for Sunday School and Devotional Meeting. (New York: Horace Waters, 1865)

- Contributions to Musical Leaves for Sabbath Schools (Cincinnati: Philip Phillips, 1865)

- "Happy golden days," solo or duet with chorus (New York: Horace Waters, 1866) N.B. Not the same as "Happy golden years" from Laura Ingalls Wilder books!

- Editor, Chapel Melodies (New York: Biglow & Main, 1868)

- Contributions to Song Life for Sunday School, ed. Philip Phillips (New York: Harper, 1872)

- Editor, Songs of Grace and Glory (New York: Horace Waters, 1874)

- Contributions to Echoes from Zion, ed. William F. Sherwin (New York: Horace Waters, 1874)

- Contributions to Singing Annual for Sabbath Schools, ed. Philip Phillips (New York: A. S. Barnes, 1874)

- Contributions to Royal Songs: For Sunday Schools and Families (New York: American Tract Society, 1875)

- Contributions to Gospel Hymns no. 2, ed. Bliss & Sankey (New York: Biglow & Main, 1876)

- Contributions to Good News (New York: C.H. Ditson, 1876)

According to Robert Lowry's biographical sketch of Fanny Crosby, Vail began working with her in 1872.(Crosby, Bells, 18) They wrote at least a half-dozen songs together:

"Close to Thee" (Songs of Grace and Glory, 1874)

"Where is thy refuge, dear brother?" (Echoes from Zion, 1874)

"Royal Songs" (Royal Songs, 1875)

"The palace of the King" (Gospel Songs no. 2, 1876)

"O be saved" (Good News, 1876)

"The guiding hand" (Good News, 1876)

Except for the first, none of these are in common use today. Vail's other hymn that has lasted to our time is "The Gate Ajar," with text by Lydia Baxter, written in 1872.(Hymnary.org) Of the two musical works, "The Gate Ajar" with its folksy pentatonic scale seems less dated; and in my opinion, the chorus of "Close to Thee" adds nothing to to Crosby's hymn. In fact, the hymn might have been better suited without a chorus at all. Sing the stanzas to another 8.7.8.7 tune, such as ST. SYLVESTER ("Father, hear the prayer we offer" in most hymnals among the U.S. Churches of Christ), and the simple beauty of the text speaks out much better.

References: Wilhoff, Mel R. "Crosby, Fanny Jane." Encyclopedia of American Gospel Music, ed. W. K. McNeil. New York: Routledge, 2005, p. 91-92.

Blumhofer, Edith L. Her Heart Can See: The Life and Hymns of Fanny J. Crosby. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 2005.

Foote, Henry Wilder. Three Centuries of American Hymnody. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1940.

Fanny Crosby's Story of Ninety-Four Years, retold by S. Trevena Jackson. New York: Revell, 1915. http://books.google.com/books?id=QsxEAAAAYAAJ

"Fanny Crosby." Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fanny_Crosby

Crosby, Fanny. Bells at Evening and Other Verses, with biographical sketch by Robert Lowry. New York: Biglow & Main, 1897. http://books.google.com/books?id=upwaAAAAYAAJ

Sankey, Ira. My Life and the Story of the Gospel Hymns and Sacred Songs. Philadelphia: Sunday School Times Press, 1907. http://books.google.com/books?id=55ICSWK_wtkC

Trow's New York City Directory, 1865 ed. http://books.google.com/books?id=hY4tAAAAYAAJ