Daniel Webster Whittle (1840-1901) was a traveling evangelist during the great wave of urban revivals in the U.S. and U.K. during the late 1800s, becoming nearly as famous as his long-time friend and associate Dwight L. Moody. And just as Moody had Sankey, Whittle had his songleading partners: he recruited Phillip Paul Bliss (1838-1876) as his first "singing evangelist" (Bliss Memoirs 42ff., 49), and after Bliss's untimely death, persuaded James McGranahan (1840-1907) away from his intended opera career (McGranahan obituary 6). Whittle himself contributed lyrics that have remained popular for more than a century--"I know Whom I have believed" (1883), "The banner of the cross" (1887), and "Why not now?" (1891)--but his promotion of the careers of Bliss and McGranahan ultimately had an even greater impact on the development of the late 19th-century gospel style.

In preparing to write on the song "Dying with Jesus" (or "Moment by moment"), which Whittle co-wrote with his daughter May Whittle Moody, I realized that my background material on his life was quickly growing into a lengthy post on its own. Whittle's personal story is the stuff of legend; so much so, in fact, that it is difficult to separate fact from fiction as it has been handed down through the years. One particular area of confusion is his service during the Civil War, the facts of which are dramatic enough without embellishment. I have done my best to clear up some of the details using original sources and contemporary testimony.

1. Was Whittle a non-believer until he prayed with a dying soldier at Vicksburg? No. As the legend goes: Whittle was reading a Bible to pass the time while recuperating from his own injuries, and a doctor asked him to pray with a dying soldier. Whittle objected that he was not actually a Christian, but agreed to try to comfort his fellow soldier, and was so moved by the dying man's faith that he himself determined to follow Christ. In reality: Whittle himself said that when he first came to Chicago in 1857--at the age of 17!--he attended the First Congregational Church, a natural choice for the Massachusetts native. Then, in his own words, Whittle was "converted" in 1860 while attending meetings of the Young Men's Christian Association at what is today the "Chicago Temple" Methodist church. He was active in the Y.M.C.A. for many years (Historical Sketch 27).

Whittle served in the 72nd Illinois Infantry during the Civil War, and after the chaplain resigned, Whittle and others organized a Y.M.C.A. within the regiment to look to its spiritual needs (Historical Sketch 28). The muster rolls held by the Illinois State Archives show that this regiment's chaplain, Henry E. Barnes, was honorably discharged on 20 June 1863 and apparently not replaced, supporting Whittle's recollection of events (Illinois Muster Rolls).

The story of praying with the dying soldier could however be based in some fact. Whittle was indeed wounded at Vicksburg on 22 May 1863 (Illinois Muster Rolls detail report #273665). Part of his recuperation was spent back in Chicago, but he left to return to his regiment at Vicksburg on 16 June (Chicago Tribune 12 June 1863 page 4). Since the chaplain was discharged four days later, Whittle may well have been called upon to attend to the soldiers' spiritual needs after his return; and as Whittle was not formally ordained, he might well have said that he was not really qualified for chaplain duties. Finally, his presence during the remaining two weeks of the Vicksburg siege, when he was still unfit for combat and the regiment needed a chaplain, makes it likely that he did spend time praying with wounded and dying soldiers at this time.

2. Did Whittle recruit a company of soldiers, and was he their captain through the Civil War? Yes and no. Though Whittle did not volunteer at the beginning of the war, one event in particular may have moved him to reconsider--the death of his friend Daniel W. Farnham at Shiloh. The Chicago Tribune noticed shortly afterward that, "The members of the Chicago Literary Union, to which society the deceased belonged, are requested to call upon D. W. Whittle at office of the American Express Company, to make arrangements for bringing the remains of Mr. Farnham to Chicago for interment" (Chicago Tribune 15 April 1862 page 472). On 16 July Whittle was at a meeting of the Union Defense Committee, representing young men of the city interested in forming a regiment. Whittle's group set an organization meeting for 18 July at Bryan Hall, where the Y.M.C.A. met (Chicago Tribune 17 July 1862 page 4). By 8 August 1862 this drive had led to the formation of six companies, one of which was Whittle's (at that date he had registered 62 recruits). The leaders of these companies, not yet officially incorporated into the Illinois Volunteer forces, were provisionally referred to as "captains" (Chicago Tribune 8 Aug 1862 page 4).

Though the companies raised by Whittle and his associates were recruited under the auspices of the Y.M.C.A., they were consolidated with companies raised by the Chicago Board of Trade to form the 72nd Illinois Infantry, known afterward as the "Chicago Board of Trade Regiment" (Historical Sketch 28). When the regiment mustered in on 21 August the men in Company B elected Whittle one of their officers. He was actually commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant, third in command under a 1st Lieutenant and the Captain (Detail report #273665). Eddy's Patriotism of Illinois records that Whittle later served as "acting adjutant" of the regiment headquarters staff (469); the muster rolls of the headquarters company show that the original adjutant, Ebenezer Bacon, passed away on 16 January 1863 (Illinois Muster Rolls). Whittle was promoted to 1st Lieutenant of Company B on 10 June 1863, following his leadership in the 22 May assault on Vicksburg (Detail report #273664).

During the regiment's reorganization after its heavy casualties at Vicksburg, Whittle was promoted to Captain (this time as a fully commissioned officer) and placed in command of Company G on 15 August 1863. He remained on the rolls of the 72nd Illinois Infantry through the end of the war and was discharged 7 August 1865 (Detail report #273666). Whittle was not with them, however, the entire time; on 11 June 1864 he was appointed Assistant Provost Marshal-General of the headquarters staff of General Otis O. Howard, who was soon to be commander of the Army of the Tennessee (OR 38/4:461). Whittle was, however, in the field with the 72nd Illinois during one of its bloodiest days of fighting--22 May 1863 at Vicksburg, Mississippi.

3. Did Whittle lose his arm in combat? No. At Vicksburg on 22 May 1863 the 72nd Illinois Infantry was part of Thomas Ransom's Brigade in McPherson's XVII Corps, the middle of three corps facing Vicksburg's fortifications from the east (Battle and Siege of Vicksburg). After an unsuccessful assault on 19 May, General Grant ordered a second attempt on 22 May. At one point Ransom's Brigade on the extreme right of McPherson's XVII Corps joined with Giles Smith's Brigade on the extreme left of Sherman's XV Corps, and made an attempt on the Confederate defenses between Graveyard Road and Jackson Road. (On a personal aside, Whittle's position was almost right next to the 8th Missouri Infantry (U.S.), in which my great-great-grandfather McMannis served--he was taken ill before Vicksburg, however, and was not present. My great-great-uncle James Hamrick was in fact present, but on the other side of the fortifications with the 36th Georgia Infantry.)

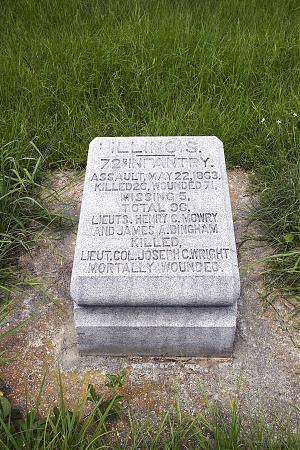

According to Adam Badeau, one of Grant's staff officers at the time, "the ground over which they passed is the most difficult about Vicksburg" (1:313-314). Things went very badly, very quickly. Two of the five regiments in the brigade lost their commanders, one killed and the other incapacitated (Eddy 469), and the loss of officers at the company level was also high. Whittle's 72nd Illinois Infantry suffered the greatest number killed overall, and its second-in-command, Lieutenant Colonel Wright, was mortally wounded (Rood 303-304).

According to Eddy's Patriotism of Illinois, Whittle, who was Acting Adjutant of the regiment and thus attached to the headquarters staff, "moved up to the assault with a smile, saying: 'Come on, my brave fellows, rebel bullets can not hit us!'" (Eddy 468-9). Whether these were his actual words or not, they proved incorrect. Whittle's record at the time of the engagement shows that he was "wounded at Vicksburg May 22, 1863 severely in [the] arm" (Detail report #273665). Amputation in such cases was common enough; but his new service record following his promotion to captain, 15 August 1863, says "slightly wounded at Vicksburg Miss. May 22, 1863" (Detail report #273666). Even by the standards of the iron men of those days, an amputation would have to be described as more than "slightly wounded!"

Whatever his injury, it was serious enough that he was sent home to Chicago for a couple of weeks, as evidenced by the following items in the Chicago Tribune:

This supports the events recounted by Jacob Hall's Biography of Gospel Song and Hymn Writers in which Whittle, home on leave, met with Dwight Moody (not, however, for the first time, as Hall states--see Historical Sketch 27). In his own words (unfortunately not sourced), Whittle was "still weak from loss of blood and with my arm in a sling" (Hall 186). This agrees with the report of Whittle's regimental commander Colonel Staring, in a letter written the day after the battle, that Whittle was "shot through the arm" (Chicago Tribune 5 June 1863 page 2). This must have caused extensive bleeding, but if the wound was through Whittle's arm it probably did less permanent damage. It also spared him the even greater danger of having a bullet extracted by the regimental surgeon, with the attendant risk of infection! And if Hall's report of Whittle's words is accurate, his arm was "in a sling," injured but intact.

Regardless of the extent of his wounds on 22 May 1863, Whittle's actions were courageous in the face of a nearly hopeless situation. He took the lead and pressed forward, knowing that he would likely meet the same fate as the men who had gone before him. General Thomas Ransom's after-action report for his brigade noted "Adjutant Whittle" of the 72nd Illinois for special commendation (Official Records 24/2:298).

4. Was Whittle ever a prisoner of war? Not as far as I can tell. It is hard to prove a negative, of course, but becomes nigh unto impossible when the question involves prisoner-of-war status in the Civil War. The records of the prisoner-of-war camps in the Confederate States are often fragmentary or lost; there is also the possibility of capture in the field with a subsequent escape or exchange that was not documented. That said, I have found no reference to Whittle being a prisoner beyond unsourced anecdotes written in the 20th century.

There are at least two possibilities for the source of this idea. In the records made available at Civil War Prisons, 56 soldiers from Whittle's regiment, the 72nd Illinois Infantry, are listed in the prison camp at Andersonville, Georgia. All but a dozen of these were captured on 30 November 1864 at the Battle of Franklin, Tennessee. Whittle, however, was not present at the battle, having been reassigned to the headquarters staff of General Oliver O. Howard on June 11 of that year (OR 38/4:461). At the time the 72nd Illinois was engaged at the Battle of Franklin, Whittle was with Howard's Army of the Tennessee near Clifton, Georgia (OR 44:603-604).

Another possible source of confusion is the fact that Whittle was significantly involved in the supervision of Confederate prisoners of war. On 16 July 1863, a week and a half after the surrender of Vicksburg, General Ransom sent Whittle from Natchez, Mississippi back to XVII Corps headquarters in charge of a group of Confederate prisoners of war (OR 24/2:682). Later, in his role as Assistant Provost Marshal General (supervisor of military police activities) of the Army of the Tennessee, he was responsible for overseeing the treatment of prisoners of war in custody of that command. General Howard's report dated 28 December 1864 on operations in Savannah includes this paragraph:

General Howard was sometimes called the "Christian general" because of his strict piety and attempt to guide his command by Christian principles (Wikipedia). Howard later recalled Whittle as "my beloved staff officer and companion" (American-Spanish War 460). No doubt he found in him a kindred spirit and believed he would deal fairly with prisoners of war and with the civilian population under military occupation.

5. Was Whittle involved in Sherman's "March to the Sea?" Yes. This is confusing, because Whittle remained on the rolls of the 72nd Illinois throughout the war; and though that regiment was meant to join with Sherman's forces during October 1864, they arrived too late. The 72nd remained behind as part of a "Detachment of the Army of the Tennessee" and fought alongside the Army of the Cumberland in the Battles of Nashville and Franklin. They remained in the Western half of the theater for the duration of the war (Adjutant General Report 2:210-211).

But Whittle was on General Howard's staff from at least 11 June 1864 onward, when Howard was commanding IV Corps of the Army of the Cumberland in the early battles of the Atlanta campaign. After the death of General McPherson in late July, Sherman appointed Howard over the Army of the Tennessee, a position he held during the March to the Sea. Military correspondence from Whittle includes a letter to Howard dated 5 October 1864 from Marietta, Georgia, just north of Atlanta (OR 39/3:96), and a letter from near Savannah, Georgia on 8 January 1865 (OR 47/2:25-26), showing just how swiftly this scorched earth campaign unfolded. Whittle's letters to Howard usually passed military intelligence gleaned from his interaction with prisoners of war, deserters, and the civilian population, in the course of his duties.

6. Did Whittle witness Sherman's communications with Federal forces at Allatoona Pass, later the basis for the song "Hold the Fort"? Maybe. After the fall of Atlanta, Confederate General Hood moved to cut Sherman's supply line, particularly the railroad leading down from Chattanooga. At the beginning of October 1864 the Allatoona Pass became a crucial prize, because the high ground and narrow passage could be held at length by whichever side took the position with sufficient forces. Federal defenders being badly outnumbered at first, General Sherman sent General Corse to reinforce them, with more troops on the way. U.S. Army Signal Corpsmen atop Kennesaw Mountain communicated by flags with the Allatoona defenders, twenty miles away, to keep them apprised of the situation. Army records show that on 4 October 1864 the following message was sent: "General Sherman says hold fast. We are coming." (Scheips 1-3).

Years later, Whittle related this event as an illustration of the need for Christians to remember that, however beleaguered we may become in our fight against temptation, divine help is close at hand. Philip Bliss heard Whittle use this in a sermon, and wrote his famous song, "Hold the fort, for I am coming!" based on Whittle's recollection of the wording Sherman's message (Bliss Memoirs 68-70).

In 1971 Paul J. Scheips published a thoroughly researched study of this song, titled "Hold the fort! The story of a song from the sawdust trail to the picket line," in the series Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology. He notes that none of the three known messages signaled from Kennesaw Mountain said, "Hold the fort, I am coming," in exactly those words. Other details of Whittle's recollection were blurred as well; he gave the Federal strength at 1,500 men against 6,000 Confederates, when the true numbers were closer to 2,000 and 3,200 respectively--misremembering the odds, "as any old soldier might have done" (Scheips 9). Refining of the verbiage of a famous statement is another of the transformations a tale often undergoes in the retelling.

But could Whittle have witnessed this scene firsthand? Scheips notes that Whittle never claimed to have been at Kennesaw Mountain, though General Howard said he was; and Howard's statement was given in a letter written in 1899, more than thirty years after the event (Scheips 8-9). The U.S. Army's records of correspondence do however preserve a statement recorded by Whittle at the "Headquarters of the Department & Army of the Tennessee, in the field, near Marietta," concerning intelligence gathered from a Confederate deserter who arrived sometime after 5 p.m. on 5 October 1864 (OR 39/3:95-96). Kennesaw Mountain is a mere 5 miles from the Marietta town square, so Whittle might easily have been up to the mountain during the battle.

General Howard's autobiography, which accurately quotes nearly all of the signal messages found by Scheips in the official U.S. Army records (2:58-62), claims that Sherman sent his first messages on 4 October by dispatch from Vining's Station (southeast of Marietta) to Kennesaw Mountain, where they were signaled across to Allatoona Pass (2:57ff.). This gives a rather different but hardly surprising picture of the communication process, in which messages went through multiple hands. Whittle's presence at Howard's headquarters on the date in question makes it easily conceivable that he saw or heard the messages as they passed through the chain of command. Whether he remembered them accurately five years later is another matter!

In Whittle's case, he was mustered out of service on 7 August 1865, well after the conclusion of hostilities, as a captain in the 72nd Illinois Infantry (Detail report #273666). Since his brevet rank of major was awarded in October, he never actually served with that rank. For this reason he is sometimes referred to as "Major" Whittle (with quotes) in older sources, when the practice of post-war brevet ranks was quite familiar. His pension record with the U.S. Veterans Administration, filed July 1899, records his rank and service as "Capt., Company G, 72nd Reg., Ill. Inf. (Organization Index). This is identical to Whittle's self-identification in a notarized letter from 1868, written to support the pension application of the widow of John F. Schellhorn, one of his soldiers from Company G (Case files WC108741). Whittle's signature is pictured below, with the rank described as "Late Capt., G Co., 72nd Reg. Ill. Infy."

But in informal usage, especially when being introduced as a speaker, no doubt it was "Major Whittle" most of the time. His service as provost marshal to the Army of the Tennessee was certainly equal to the rank, even if it was never officially granted during the war, so it was nothing if not appropriate in ceremonial usage.

Uncovering the truth about some of the details of Whittle's life has proven yet again the tendency for the stories of beloved songs and beloved songwriters to "grow in the telling." The ability to access primary sources online has made it easier now to look back--however imperfectly--past the traditions and legends that grow around these things. In the case of Daniel W. Whittle, even if the truth was not quite as dramatic in some points as the legend, we find a man who exhibited courage, responsibility, and a lifelong commitment to serving the spiritual needs of his fellow human beings.

References:

The American-Spanish War: a history by the war leaders. Norwich, Conn.: Haskell & Son, 1899.

http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009559221

Badeau, Adam. Military history of Ulysses S. Grant: from April, 1861, to April, 1865. 3 volumes. New York: Appleton, 1881.

Volume 1: http://archive.org/details/militaryhistory02badegoog

Volume 2: http://archive.org/details/militaryhistory03badegoog

Volume 3: http://archive.org/details/militaryhistory00badegoog

Battle and siege of Vicksburg, MS: May 18-July 4, 1863 (map). Civil War Trust.

http://www.civilwar.org/battlefields/vicksburg/maps/vicksburgmap.html

Bielakowski, Alexander M. "Brevet rank." Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: a political, social, and military history, ed. David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: Norton, 2000.

Case files of approved pension applications of widows and other veterans... 1861-1934. United States Veterans Administration. ARC Identifier 300020.

Chicago Tribune 9 November 1861 page 4. "The City."

Chicago Tribune 15 April 1862 page 472. "The City."

Chicago Tribune 29 April 1862 page 546. "Chicago Literary Union."

Chicago Tribune 17 July 1862 page 4. "Meeting of the Union Defense Committee."

Chicago Tribune 8 Aug 1862 page 4. "Progress of recruiting."

Chicago Tribune 5 June 1863 page 2. Letter from Thomas A. Staring, 23 May 1863.

Chicago Tribune 12 June 1863 page 4. "The City."

http://www.archive.org/stream/historicalsketch00smit#page/n9/mode/2up

Howard, Oliver Otis. Autobiography, 2 volumes. New York: Baker & Taylor, 1908.

Volume 1: http://archive.org/details/autobiographyofo01inhowa

Volume 2: http://archive.org/details/autobiographyofo02inhowa

Illinois Civil War muster and descriptive rolls. Illinois State Archives.

http://www.ilsos.gov/isaveterans/civilmustersrch.jsp

"The late Major D. W. Whittle." Record of Christian work 20:4 (April 1901), 241-242. http://books.google.com/books?id=zQ0GVxoRbkIC&pg=PA241

McGranahan obituary pamphlet. http://www.archive.org/stream/jamesmcgranahanb00pitt#page/n5/mode/2up

Memoirs of Philip P. Bliss, ed. Daniel Webster Whittle. New York: A. S. Barnes, 1877.

http://openlibrary.org/books/OL7061061M/Memoirs_of_Philip_P._Bliss.

Official records of the War of the Rebellion. Washington, D.C.: War Records Publication Office, 1881-1901. Online full-text version provided in the Making of America Collection, Cornell University Library.

http://ebooks.library.cornell.edu/m/moawar/waro_fulltext.html

"Oliver O. Howard." Wikipedia. Viewed 28 January 2013. (Citations provided in article.)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oliver_O._Howard

Organization index to pension files of veterans who served between 1861 and 1900. United States Veterans Administration. ARC Identifier 2588825.

Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Illinois, 9 volumes. Springfield, Ill.: Phillips Bros., 1900.

http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000050178

Rood, Hosea W. Wisconsin at Vicksburg. Madison, Wisconsin: Wisconsin-Vicksburg Monument Commission, 1914.

http://books.google.com/books?id=1JxAAAAAYAAJ

Scheips, Paul J. Hold the fort! The story of a song from the sawdust trail to the picket line. Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1971. http://www.sil.si.edu/smithsoniancontributions/HistoryTechnology/pdf_hi/SSHT-0009.pdf

"Whittle, Daniel W." (Record #273664). Illinois Civil War detail reports. Illinois State Archives. http://www.ilsos.gov/isaveterans/civilMusterSearch.do?key=273664

"Whittle, Daniel W." (Record #273665). Illinois Civil War detail reports. Illinois State Archives.

In preparing to write on the song "Dying with Jesus" (or "Moment by moment"), which Whittle co-wrote with his daughter May Whittle Moody, I realized that my background material on his life was quickly growing into a lengthy post on its own. Whittle's personal story is the stuff of legend; so much so, in fact, that it is difficult to separate fact from fiction as it has been handed down through the years. One particular area of confusion is his service during the Civil War, the facts of which are dramatic enough without embellishment. I have done my best to clear up some of the details using original sources and contemporary testimony.

|

| Daniel Webster Whittle in his younger days. Scheips, page 7. Photo from Library of Congress. |

1. Was Whittle a non-believer until he prayed with a dying soldier at Vicksburg? No. As the legend goes: Whittle was reading a Bible to pass the time while recuperating from his own injuries, and a doctor asked him to pray with a dying soldier. Whittle objected that he was not actually a Christian, but agreed to try to comfort his fellow soldier, and was so moved by the dying man's faith that he himself determined to follow Christ. In reality: Whittle himself said that when he first came to Chicago in 1857--at the age of 17!--he attended the First Congregational Church, a natural choice for the Massachusetts native. Then, in his own words, Whittle was "converted" in 1860 while attending meetings of the Young Men's Christian Association at what is today the "Chicago Temple" Methodist church. He was active in the Y.M.C.A. for many years (Historical Sketch 27).

Whittle served in the 72nd Illinois Infantry during the Civil War, and after the chaplain resigned, Whittle and others organized a Y.M.C.A. within the regiment to look to its spiritual needs (Historical Sketch 28). The muster rolls held by the Illinois State Archives show that this regiment's chaplain, Henry E. Barnes, was honorably discharged on 20 June 1863 and apparently not replaced, supporting Whittle's recollection of events (Illinois Muster Rolls).

The story of praying with the dying soldier could however be based in some fact. Whittle was indeed wounded at Vicksburg on 22 May 1863 (Illinois Muster Rolls detail report #273665). Part of his recuperation was spent back in Chicago, but he left to return to his regiment at Vicksburg on 16 June (Chicago Tribune 12 June 1863 page 4). Since the chaplain was discharged four days later, Whittle may well have been called upon to attend to the soldiers' spiritual needs after his return; and as Whittle was not formally ordained, he might well have said that he was not really qualified for chaplain duties. Finally, his presence during the remaining two weeks of the Vicksburg siege, when he was still unfit for combat and the regiment needed a chaplain, makes it likely that he did spend time praying with wounded and dying soldiers at this time.

2. Did Whittle recruit a company of soldiers, and was he their captain through the Civil War? Yes and no. Though Whittle did not volunteer at the beginning of the war, one event in particular may have moved him to reconsider--the death of his friend Daniel W. Farnham at Shiloh. The Chicago Tribune noticed shortly afterward that, "The members of the Chicago Literary Union, to which society the deceased belonged, are requested to call upon D. W. Whittle at office of the American Express Company, to make arrangements for bringing the remains of Mr. Farnham to Chicago for interment" (Chicago Tribune 15 April 1862 page 472). On 16 July Whittle was at a meeting of the Union Defense Committee, representing young men of the city interested in forming a regiment. Whittle's group set an organization meeting for 18 July at Bryan Hall, where the Y.M.C.A. met (Chicago Tribune 17 July 1862 page 4). By 8 August 1862 this drive had led to the formation of six companies, one of which was Whittle's (at that date he had registered 62 recruits). The leaders of these companies, not yet officially incorporated into the Illinois Volunteer forces, were provisionally referred to as "captains" (Chicago Tribune 8 Aug 1862 page 4).

Though the companies raised by Whittle and his associates were recruited under the auspices of the Y.M.C.A., they were consolidated with companies raised by the Chicago Board of Trade to form the 72nd Illinois Infantry, known afterward as the "Chicago Board of Trade Regiment" (Historical Sketch 28). When the regiment mustered in on 21 August the men in Company B elected Whittle one of their officers. He was actually commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant, third in command under a 1st Lieutenant and the Captain (Detail report #273665). Eddy's Patriotism of Illinois records that Whittle later served as "acting adjutant" of the regiment headquarters staff (469); the muster rolls of the headquarters company show that the original adjutant, Ebenezer Bacon, passed away on 16 January 1863 (Illinois Muster Rolls). Whittle was promoted to 1st Lieutenant of Company B on 10 June 1863, following his leadership in the 22 May assault on Vicksburg (Detail report #273664).

During the regiment's reorganization after its heavy casualties at Vicksburg, Whittle was promoted to Captain (this time as a fully commissioned officer) and placed in command of Company G on 15 August 1863. He remained on the rolls of the 72nd Illinois Infantry through the end of the war and was discharged 7 August 1865 (Detail report #273666). Whittle was not with them, however, the entire time; on 11 June 1864 he was appointed Assistant Provost Marshal-General of the headquarters staff of General Otis O. Howard, who was soon to be commander of the Army of the Tennessee (OR 38/4:461). Whittle was, however, in the field with the 72nd Illinois during one of its bloodiest days of fighting--22 May 1863 at Vicksburg, Mississippi.

3. Did Whittle lose his arm in combat? No. At Vicksburg on 22 May 1863 the 72nd Illinois Infantry was part of Thomas Ransom's Brigade in McPherson's XVII Corps, the middle of three corps facing Vicksburg's fortifications from the east (Battle and Siege of Vicksburg). After an unsuccessful assault on 19 May, General Grant ordered a second attempt on 22 May. At one point Ransom's Brigade on the extreme right of McPherson's XVII Corps joined with Giles Smith's Brigade on the extreme left of Sherman's XV Corps, and made an attempt on the Confederate defenses between Graveyard Road and Jackson Road. (On a personal aside, Whittle's position was almost right next to the 8th Missouri Infantry (U.S.), in which my great-great-grandfather McMannis served--he was taken ill before Vicksburg, however, and was not present. My great-great-uncle James Hamrick was in fact present, but on the other side of the fortifications with the 36th Georgia Infantry.)

|

| View this location in Wikimapia. |

According to Eddy's Patriotism of Illinois, Whittle, who was Acting Adjutant of the regiment and thus attached to the headquarters staff, "moved up to the assault with a smile, saying: 'Come on, my brave fellows, rebel bullets can not hit us!'" (Eddy 468-9). Whether these were his actual words or not, they proved incorrect. Whittle's record at the time of the engagement shows that he was "wounded at Vicksburg May 22, 1863 severely in [the] arm" (Detail report #273665). Amputation in such cases was common enough; but his new service record following his promotion to captain, 15 August 1863, says "slightly wounded at Vicksburg Miss. May 22, 1863" (Detail report #273666). Even by the standards of the iron men of those days, an amputation would have to be described as more than "slightly wounded!"

Whatever his injury, it was serious enough that he was sent home to Chicago for a couple of weeks, as evidenced by the following items in the Chicago Tribune:

A Worthy Compliment. The Chicago Literary Union, we understand, purpose giving gallant Lieut. Whittle, of the 72d Regiment, a complimentary supper, at the Briggs House, on Saturday evening of the present week. It is a compliment worthily bestowed.

For the Seventy-Second. Lieut. Whittle, of the 77d [72nd DRH], will return to his regiment, on Tuesday, next, and will take with him any letters addressed to that regiment, if left at the American Express Office by next Monday (12 June 1863 page 4).

Regardless of the extent of his wounds on 22 May 1863, Whittle's actions were courageous in the face of a nearly hopeless situation. He took the lead and pressed forward, knowing that he would likely meet the same fate as the men who had gone before him. General Thomas Ransom's after-action report for his brigade noted "Adjutant Whittle" of the 72nd Illinois for special commendation (Official Records 24/2:298).

4. Was Whittle ever a prisoner of war? Not as far as I can tell. It is hard to prove a negative, of course, but becomes nigh unto impossible when the question involves prisoner-of-war status in the Civil War. The records of the prisoner-of-war camps in the Confederate States are often fragmentary or lost; there is also the possibility of capture in the field with a subsequent escape or exchange that was not documented. That said, I have found no reference to Whittle being a prisoner beyond unsourced anecdotes written in the 20th century.

There are at least two possibilities for the source of this idea. In the records made available at Civil War Prisons, 56 soldiers from Whittle's regiment, the 72nd Illinois Infantry, are listed in the prison camp at Andersonville, Georgia. All but a dozen of these were captured on 30 November 1864 at the Battle of Franklin, Tennessee. Whittle, however, was not present at the battle, having been reassigned to the headquarters staff of General Oliver O. Howard on June 11 of that year (OR 38/4:461). At the time the 72nd Illinois was engaged at the Battle of Franklin, Whittle was with Howard's Army of the Tennessee near Clifton, Georgia (OR 44:603-604).

Another possible source of confusion is the fact that Whittle was significantly involved in the supervision of Confederate prisoners of war. On 16 July 1863, a week and a half after the surrender of Vicksburg, General Ransom sent Whittle from Natchez, Mississippi back to XVII Corps headquarters in charge of a group of Confederate prisoners of war (OR 24/2:682). Later, in his role as Assistant Provost Marshal General (supervisor of military police activities) of the Army of the Tennessee, he was responsible for overseeing the treatment of prisoners of war in custody of that command. General Howard's report dated 28 December 1864 on operations in Savannah includes this paragraph:

Capt. D. W. Whittle, assistant provost-marshal-general, receives my hearty approbation for his activity in discharging the public duties of his department, for his careful record and disposition of prisoners, and for his unremitting attention to the comfort and interest of myself and staff; while acting in his capacity of commandant of headquarters (OR 44:74-75)

5. Was Whittle involved in Sherman's "March to the Sea?" Yes. This is confusing, because Whittle remained on the rolls of the 72nd Illinois throughout the war; and though that regiment was meant to join with Sherman's forces during October 1864, they arrived too late. The 72nd remained behind as part of a "Detachment of the Army of the Tennessee" and fought alongside the Army of the Cumberland in the Battles of Nashville and Franklin. They remained in the Western half of the theater for the duration of the war (Adjutant General Report 2:210-211).

But Whittle was on General Howard's staff from at least 11 June 1864 onward, when Howard was commanding IV Corps of the Army of the Cumberland in the early battles of the Atlanta campaign. After the death of General McPherson in late July, Sherman appointed Howard over the Army of the Tennessee, a position he held during the March to the Sea. Military correspondence from Whittle includes a letter to Howard dated 5 October 1864 from Marietta, Georgia, just north of Atlanta (OR 39/3:96), and a letter from near Savannah, Georgia on 8 January 1865 (OR 47/2:25-26), showing just how swiftly this scorched earth campaign unfolded. Whittle's letters to Howard usually passed military intelligence gleaned from his interaction with prisoners of war, deserters, and the civilian population, in the course of his duties.

.bmp) |

| The railroad cut at Allatoona Pass, inspiration for the song "Hold the fort!" Scheips, page 3. Photo from National Archives. |

6. Did Whittle witness Sherman's communications with Federal forces at Allatoona Pass, later the basis for the song "Hold the Fort"? Maybe. After the fall of Atlanta, Confederate General Hood moved to cut Sherman's supply line, particularly the railroad leading down from Chattanooga. At the beginning of October 1864 the Allatoona Pass became a crucial prize, because the high ground and narrow passage could be held at length by whichever side took the position with sufficient forces. Federal defenders being badly outnumbered at first, General Sherman sent General Corse to reinforce them, with more troops on the way. U.S. Army Signal Corpsmen atop Kennesaw Mountain communicated by flags with the Allatoona defenders, twenty miles away, to keep them apprised of the situation. Army records show that on 4 October 1864 the following message was sent: "General Sherman says hold fast. We are coming." (Scheips 1-3).

Years later, Whittle related this event as an illustration of the need for Christians to remember that, however beleaguered we may become in our fight against temptation, divine help is close at hand. Philip Bliss heard Whittle use this in a sermon, and wrote his famous song, "Hold the fort, for I am coming!" based on Whittle's recollection of the wording Sherman's message (Bliss Memoirs 68-70).

In 1971 Paul J. Scheips published a thoroughly researched study of this song, titled "Hold the fort! The story of a song from the sawdust trail to the picket line," in the series Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology. He notes that none of the three known messages signaled from Kennesaw Mountain said, "Hold the fort, I am coming," in exactly those words. Other details of Whittle's recollection were blurred as well; he gave the Federal strength at 1,500 men against 6,000 Confederates, when the true numbers were closer to 2,000 and 3,200 respectively--misremembering the odds, "as any old soldier might have done" (Scheips 9). Refining of the verbiage of a famous statement is another of the transformations a tale often undergoes in the retelling.

But could Whittle have witnessed this scene firsthand? Scheips notes that Whittle never claimed to have been at Kennesaw Mountain, though General Howard said he was; and Howard's statement was given in a letter written in 1899, more than thirty years after the event (Scheips 8-9). The U.S. Army's records of correspondence do however preserve a statement recorded by Whittle at the "Headquarters of the Department & Army of the Tennessee, in the field, near Marietta," concerning intelligence gathered from a Confederate deserter who arrived sometime after 5 p.m. on 5 October 1864 (OR 39/3:95-96). Kennesaw Mountain is a mere 5 miles from the Marietta town square, so Whittle might easily have been up to the mountain during the battle.

General Howard's autobiography, which accurately quotes nearly all of the signal messages found by Scheips in the official U.S. Army records (2:58-62), claims that Sherman sent his first messages on 4 October by dispatch from Vining's Station (southeast of Marietta) to Kennesaw Mountain, where they were signaled across to Allatoona Pass (2:57ff.). This gives a rather different but hardly surprising picture of the communication process, in which messages went through multiple hands. Whittle's presence at Howard's headquarters on the date in question makes it easily conceivable that he saw or heard the messages as they passed through the chain of command. Whether he remembered them accurately five years later is another matter!

7. Was his rank actually "Major Whittle," as he was commonly called after the war? Yes, "but." Whittle was breveted as a major by General Order 148, 14 October 1865, for "faithful and meritorious service during the campaign against the city of Mobile and its defences." (Scheips 47). "Brevet rank" was a term of considerable confusion. Officially, it was honorary, not affecting actual responsibilities or pay; but sometimes a man was breveted as a matter of decorum, especially if serving in a position usually reserved for a higher rank (for example a lieutenant commanding a company instead of a captain). Some officers held a brevet rank at the level of their actual responsibilities, but were never officially promoted, and remained a grade or two lower in official rank. The majority of brevet ranks, however, were conferred at the end of the war as rewards for meritorious service (Bielakowski).

In Whittle's case, he was mustered out of service on 7 August 1865, well after the conclusion of hostilities, as a captain in the 72nd Illinois Infantry (Detail report #273666). Since his brevet rank of major was awarded in October, he never actually served with that rank. For this reason he is sometimes referred to as "Major" Whittle (with quotes) in older sources, when the practice of post-war brevet ranks was quite familiar. His pension record with the U.S. Veterans Administration, filed July 1899, records his rank and service as "Capt., Company G, 72nd Reg., Ill. Inf. (Organization Index). This is identical to Whittle's self-identification in a notarized letter from 1868, written to support the pension application of the widow of John F. Schellhorn, one of his soldiers from Company G (Case files WC108741). Whittle's signature is pictured below, with the rank described as "Late Capt., G Co., 72nd Reg. Ill. Infy."

But in informal usage, especially when being introduced as a speaker, no doubt it was "Major Whittle" most of the time. His service as provost marshal to the Army of the Tennessee was certainly equal to the rank, even if it was never officially granted during the war, so it was nothing if not appropriate in ceremonial usage.

Uncovering the truth about some of the details of Whittle's life has proven yet again the tendency for the stories of beloved songs and beloved songwriters to "grow in the telling." The ability to access primary sources online has made it easier now to look back--however imperfectly--past the traditions and legends that grow around these things. In the case of Daniel W. Whittle, even if the truth was not quite as dramatic in some points as the legend, we find a man who exhibited courage, responsibility, and a lifelong commitment to serving the spiritual needs of his fellow human beings.

|

| Daniel W. Whittle in his older years. Photo from Ira Sankey, My life and the story of the Gospel Hymns (Philadelphia: P. W. Ziegler, 1907), page 213. |

References:

The American-Spanish War: a history by the war leaders. Norwich, Conn.: Haskell & Son, 1899.

http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009559221

Badeau, Adam. Military history of Ulysses S. Grant: from April, 1861, to April, 1865. 3 volumes. New York: Appleton, 1881.

Volume 1: http://archive.org/details/militaryhistory02badegoog

Volume 2: http://archive.org/details/militaryhistory03badegoog

Volume 3: http://archive.org/details/militaryhistory00badegoog

Battle and siege of Vicksburg, MS: May 18-July 4, 1863 (map). Civil War Trust.

http://www.civilwar.org/battlefields/vicksburg/maps/vicksburgmap.html

Bielakowski, Alexander M. "Brevet rank." Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: a political, social, and military history, ed. David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: Norton, 2000.

Case files of approved pension applications of widows and other veterans... 1861-1934. United States Veterans Administration. ARC Identifier 300020.

Chicago Tribune 9 November 1861 page 4. "The City."

Chicago Tribune 15 April 1862 page 472. "The City."

Chicago Tribune 29 April 1862 page 546. "Chicago Literary Union."

Chicago Tribune 17 July 1862 page 4. "Meeting of the Union Defense Committee."

Chicago Tribune 8 Aug 1862 page 4. "Progress of recruiting."

Chicago Tribune 5 June 1863 page 2. Letter from Thomas A. Staring, 23 May 1863.

Chicago Tribune 12 June 1863 page 4. "The City."

Eddy, Thomas Mears. The Patriotism of Illinois. A Record of the Civil and Military History of the State in the War for the Union. Chicago: Clarke and Co., 1865. Digital version by Northern Illinois University. http://lincoln.lib.niu.edu/cgi-bin/philologic/navigate.pl?lincoln.5050

Hall, J. H. Biography of gospel song and hymn writers. New York: Revell, 1914.

http://openlibrary.org/books/OL13503879M/Biography_of_Gospel_song_and_hymn_writers.

Historical sketch of the Young Men's Christian Association of Chicago. Chicago: Y.M.C.A., 1898.http://openlibrary.org/books/OL13503879M/Biography_of_Gospel_song_and_hymn_writers.

http://www.archive.org/stream/historicalsketch00smit#page/n9/mode/2up

Howard, Oliver Otis. Autobiography, 2 volumes. New York: Baker & Taylor, 1908.

Volume 2: http://archive.org/details/autobiographyofo02inhowa

Illinois Civil War muster and descriptive rolls. Illinois State Archives.

http://www.ilsos.gov/isaveterans/civilmustersrch.jsp

"The late Major D. W. Whittle." Record of Christian work 20:4 (April 1901), 241-242. http://books.google.com/books?id=zQ0GVxoRbkIC&pg=PA241

McGranahan obituary pamphlet. http://www.archive.org/stream/jamesmcgranahanb00pitt#page/n5/mode/2up

Memoirs of Philip P. Bliss, ed. Daniel Webster Whittle. New York: A. S. Barnes, 1877.

http://openlibrary.org/books/OL7061061M/Memoirs_of_Philip_P._Bliss.

Official records of the War of the Rebellion. Washington, D.C.: War Records Publication Office, 1881-1901. Online full-text version provided in the Making of America Collection, Cornell University Library.

http://ebooks.library.cornell.edu/m/moawar/waro_fulltext.html

"Oliver O. Howard." Wikipedia. Viewed 28 January 2013. (Citations provided in article.)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oliver_O._Howard

Organization index to pension files of veterans who served between 1861 and 1900. United States Veterans Administration. ARC Identifier 2588825.

http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000050178

Rood, Hosea W. Wisconsin at Vicksburg. Madison, Wisconsin: Wisconsin-Vicksburg Monument Commission, 1914.

http://books.google.com/books?id=1JxAAAAAYAAJ

Scheips, Paul J. Hold the fort! The story of a song from the sawdust trail to the picket line. Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1971. http://www.sil.si.edu/smithsoniancontributions/HistoryTechnology/pdf_hi/SSHT-0009.pdf

"Whittle, Daniel W." (Record #273664). Illinois Civil War detail reports. Illinois State Archives. http://www.ilsos.gov/isaveterans/civilMusterSearch.do?key=273664

"Whittle, Daniel W." (Record #273665). Illinois Civil War detail reports. Illinois State Archives.

"Whittle, Daniel W." (Record #273666). Illinois Civil War detail reports. Illinois State Archives.