Praise for the Lord #155

Words: William Walsham How, 1864

Music: SINE NOMINE, Ralph Vaughan Williams, 1906

|

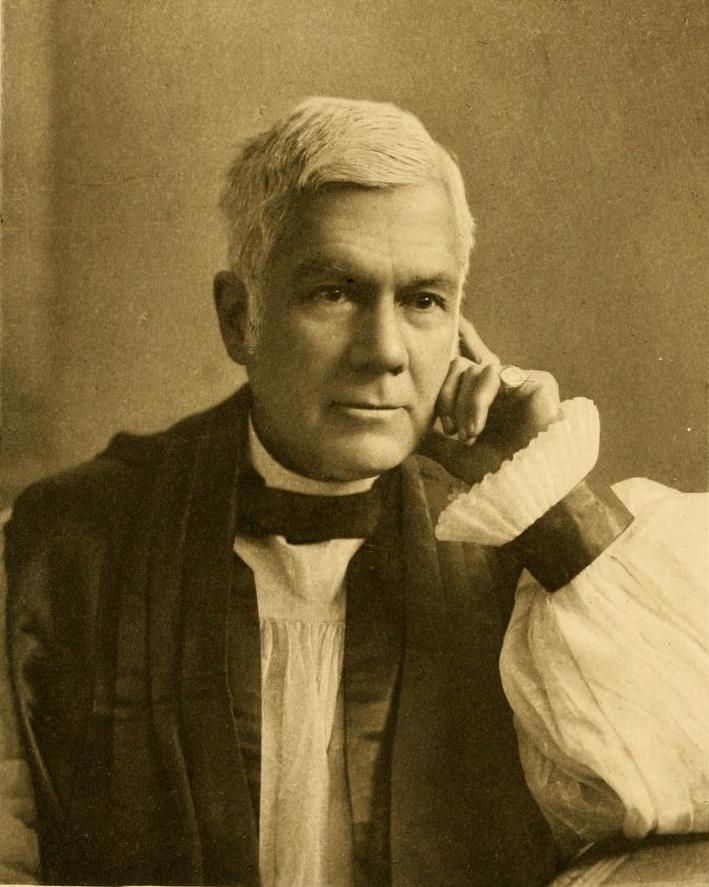

| Bishop How, c. 1870 |

William Walsham How wrote around seventy-five hymn texts, many of which continued in use for decades, and a handful of which remain in wide use today. According to Hymnary.org his most widely published text is "O Jesus, Thou art standing", found in 632 hymnals, including 21st-century examples such as the Baptist Hymnal. Other well known hymns by How, in addition to "For all the Saints", are "O Word of God incarnate" (PFTL #503) and "We give Thee but Thine own" (PFTL #724). In all of these we can see the truth of John Julian's assessment of William Walsham How's hymn-writing: "Those compositions which have laid the firmest hold upon the Church, are simple, unadorned, but enthusiastically practical hymns” (I:540).

The great poet is not necessarily a good hymn-writer. This will be apparent to any one who studies our collections of hymns. Two things will strike such a student. He will find that among the hymn-writers there are few men of first-class literary rank. He will further find that the most popular hymns are not from the pens of these few. In other words, the highest poetic gift does not ensure the power of writing a good hymn. Less gifted men succeed where men of higher endowments fail (F. D. How 412).

This reminds me of a conversation with Dr. John Parker of Lipscomb University, as he was beginning work on what would become his lovely book Abide with Me: A Photographic Journey Through Great British Hymns (New Leaf Press, 2009). As a professor of English literature he was frankly surprised at how little overlap he found between the "greats" of English literature and the "greats" of English hymn-writers; for example, Isaac Watts's foundational role in English hymnody is hardly matched by his reputation in English literature in general. (Perhaps the best known reference to Watts in the latter context is in fact poking fun at him, when Lewis Carroll has Alice misquote "How doth the little busy bee" as "How doth the little crocodile"!) And on the other hand, where are the hymns of Milton, or Donne, or Bunyan, great spiritual writers though they were in other genres? We have some fine hymns adapted from the literary greats ("Dear Lord and Father of mankind" from Whittier, for example), but they tend to be the exception. Boyd Carpenter wisely continues, however:

On the other hand, it would be a mistake to infer that success in hymn-writing needs no literary qualities. There have been cases in which men of little or no cultivated literary capacity have produced an admirable hymn; but an examination of our hymn-books will show that the bulk of our best hymns have been the work of devout men who have possessed natural poetic feeling and a cultivated taste (412).

The trick is, from Boyd Carpenter's perspective, to bring these things into balance: "Next to true devotional feeling, good sense is the first requisite of a good hymn. There are other requisites, no doubt, but eccentricity is the ruin of a hymn" (412). The congregation that sings a hymn will often consist of several well-read people but many others with only minimal exposure to or interest in literature, just as it will consist of children (physical and spiritual) and elders (physical and spiritual). The difficult task of a hymn-writer is to reach them all with something worthwhile that they can use to worship God. A thorough knowledge of and skill in literary composition gives the writer the range and depth to communicate; good sense makes sure it is used for the right purpose, rather than to show off the author's skill. This dedication to service is well summed up by Boyd Carpenter, and is high praise to his friend William Walsham How:

It is the fate of a hymn-writer to be forgotten. Of the millions who Sunday after Sunday sing hymns in our churches, not more than a few hundreds know or consider whose words they are singing. The hymn remains: the name of the writer passes away. Bishop Walsham How was prepared for this; his ambition was not to be remembered, but to be helpful. He gave free liberty to any to make use of his hymns. It was enough for him if he could enlarge the thanksgivings of the Church or minister by song to the souls of men. There will be few to doubt that his unselfish wish will be fulfilled (416).

"For all the saints" first appeared in a small collection titled Hymn for Saints’ Day and Other Hymns, published by Earl Nelson in 1864, and then (as Julian put it) "in nearly every hymnal of importance published in Great Britain" and "in the best collections of all English-speaking countries" (I:380). It is a hymn for All Saints' Day, celebrated in the Western calendar on November 1st (or by some on the first Sunday in November). Despite its original association with the veneration of saints, many Protestant groups retained the hymn as a memorial to departed Christians in general, and one could easily see this hymn used at a Homecoming Sunday, New Year's Service, or even at a funeral service. It is a topic not much addressed in our hymnals, and deserves to be used.

Stanza 1:

For all the saints, who from their labors rest,

Who Thee by faith before the world confessed,

Thy Name, O Jesus, be forever blessed.

Alleluia, Alleluia!

In the today's world the "saints" that come to most people's minds are those who are formally recognized by a religious tradition for an exceptional life of holiness and service. Admirable though many of these people are for their examples and contributions, however, this obscures the "ordinariness" of the Biblical use of the term. After all, Paul called the Christians in Corinth "saints" before proceeding to take them to the woodshed over their multiple and egregious errors! An important clue to New Testament usage of this word, in fact, is woven into Paul's opening statement of the letter:

To the church of God that is in Corinth, to those sanctified in Christ Jesus, called to be saints together with all those who in every place call upon the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, both their Lord and ours (1 Corinthians 1:2).

They are not saints by virtue of their superior holiness or service; they are "called to be saints," and not they alone, but "all those . . . in every place" who "call upon the name of our Lord Jesus Christ." They are "sanctified" (made saints), then, not by their own lives or by popular acclaim, but "in Christ Jesus." The passive voice of the phrases "sanctified in Christ Jesus" and "called to be saints" ought not to be missed, for "the holiness derives from Christ" (Kittell 1:107).

Even so, this status of being cleansed from sin and set apart for God's service ought to inspire us to such a life of holiness and service that would be worth remembering when we are gone. "To be a saint is not directly and primarily to be good but to be set apart by God as His own, yet the godly and holy character ought inevitably and immediately to result" (Estes). And certainly there is nothing wrong with remembering those saints who have set this kind of example: "Remember your leaders, those who spoke to you the word of God. Consider the outcome of their way of life, and imitate their faith" (Hebrews 13:7).

In the opening stanza of this hymn, then, we are offering our thanks to the Lord for those saints who have gone before us. They confessed Jesus before the world, making the "good confession" of belief in Jesus Christ as the Son of God and Savior (1 Timothy 6:14). The King James Version gives this as "good profession", and that is what it became (in the modern sense of the word) for these saints--their calling and purpose in life. This daily confession, by word and deed, was rooted in faith in the One confessed: "Let us hold fast the confession of our hope without wavering, for He who promised is faithful" (Hebrews 10:23). He was faithful to them in this life, and promises to be faithful in the world to come, saying, "Therefore whoever confesses Me before men, him I will also confess before My Father who is in heaven" (Matthew 10:32).

Here is a call for the endurance of the saints, those who keep the commandments of God and their faith in Jesus. And I heard a voice from heaven saying, "Write this: Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord from now on." "Blessed indeed," says the Spirit, "that they may rest from their labors, for their deeds follow them!" (Revelation 14:12-13)

In light of these things we can take heart, "always abounding in the work of the Lord, knowing that in the Lord your labor is not in vain" (1 Corinthians 15:58).

Thou wast their Rock, their Fortress and their Might;

Thou, Lord, their Captain in the well fought fight;

Thou, in the darkness drear, their one true Light.

Alleluia, Alleluia!

Though this hymn is an expression of thanksgiving and appreciation for the saints who preceded us, it is addressed to the Lord through whom they gained their victory. As one of the most famous of these saints said, "Be imitators of me, as I am of Christ" (1 Corinthians 11:1); and through this life lived in dependence on and in imitation of Christ, Paul was assured of that "crown of righteousness" at the end (2 Timothy 4:8).

William How describes the saints' reliance on Jesus using a number of metaphors from Biblical sources. The first line appears to paraphrase the opening of the lyric in 2 Samuel 22 (duplicated with minor differences as Psalm 18), which David wrote in thanksgiving for the recent victories that had secured his kingship:

The LORD is my rock and my fortress and my deliverer, my God, my rock, in whom I take refuge, my shield, and the horn of my salvation, my stronghold and my refuge, my savior; You save me from violence" (2 Samuel 22:2-3).

There is a reference to the same ideas in Psalm 61:1-3, though in a less triumphant tone:

Hear my cry, O God, listen to my prayer; from the end of the earth I call to You when my heart is faint. Lead me to the rock that is higher than I, for You have been my refuge, a strong tower against the enemy.

|

| Roman-era fort in the Judean Desert (Heritage Conservation Outside The City Pikiwiki Israel) |

In the New Testament, Jesus concludes the Sermon on the Mount with a memorable parable about the stability of rock and the instability of sand (a fact well known to his listeners, who were well familiar with flash flooding and erosion). Though the reference is to His words, rather than to himself or His Father, the meaning is the same: what is your "life founded upon? The saints whose memory is honored knew this: Everyone then who hears these words of mine and does them will be like a wise man who built his house on the rock. And the rain fell, and the floods came, and the winds blew and beat on that house, but it did not fall, because it had been founded on the rock" (Matthew 7:24-25).

The next line of this stanza compares Jesus to the Captain of an army, a metaphor also founded in Scripture. To begin with, in the King James Version Hebrews 2:10 refers to Him as "the Captain of [our] salvation." More modern translations render this as "Author", "Founder", or "Pioneer", which rightly bring out the original word's fuller meaning of a leader who blazes the way ahead of his followers; "He is the leader of all others who tread that path" (Vine 80). If we use the metaphor of a military captain to describe Him, we ought to remember that Jesus is not safely behind the lines at headquarters; like the ancient Roman centurion, He is at the head of His troops going into battle.

Though His kingdom is "not of this world" (John 18:36), and we "do not wrestle against flesh and blood" (Ephesians 6:12), the followers of Jesus have a battle to fight. Paul, who grew up in a Roman city and became personally acquainted with a number of soldiers in his lifetime, used the military metaphor often. The "well-fought fight" is the consuming purpose of the Christian life, and requires our utmost. Only near the end was Paul able to look back and say, "I have fought the good fight, I have finished the race, I have kept the faith" (2 Timothy 4:7). The stanza closes with a picture of these fighting, struggling saints pressing on through the darkness toward the light. "This present darkness" through which they fought and we still fight (Ephesians 6:12) seems overpowering, but we are assured that "the darkness is passing away and the true light is already shining" (1 John 2:8). We can overcome the darkness if we keep our focus on that undying Light. "So then let us cast off the works of darkness and put on the armor of light" (Romans 13:12).

Stanza 3:

O may Thy soldiers, faithful, true and bold,

Fight as the saints who nobly fought of old,

And win with them the victor’s crown of gold.

Alleluia, Alleluia!

How's lyric turns now to us, the soldiers still in the field, who draw encouragement from those who have gone before. As Paul fought his own "good fight," so we are to "Fight the good fight of the faith. Take hold of the eternal life to which you were called and about which you made the good confession in the presence of many witnesses" (1 Timothy 6:12). It is awe-inspiring to think of being a fellow soldier with men such as Paul, but he frequently called his co-workers in the church by these terms (Philippians 2:25, Philemon 2).

Paul also calls us to consider our responsibilities as Christians in comparison to those of earthly soldiers. Soldiers are expected to be fully committed to their mission, to the exclusion of other matters. "No soldier gets entangled in civilian pursuits, since his aim is to please the one who enlisted him" (2 Timothy 2:4). The armed forces of the U.S. rely heavily today on Reserves and the National Guard, members of which pursue their civilian occupations with occasional training periods; but when they are deployed to active duty they leave these things behind and become full-time soldiers. Christians in a sense are always on active duty, and need to focus on the mission. We do not know how long our own fight will be, or what the gains and losses will look like in the individual moment. But like the saints who went before us, we need to keep our minds on the fight, and not get bogged down with things that will hinder our service:

Since therefore Christ suffered in the flesh, arm yourselves with the same way of thinking, for whoever has suffered in the flesh has ceased from sin, so as to live for the rest of the time in the flesh no longer for human passions but for the will of God (1 Peter 4:1-2).

Part of the ongoing duty of soldiers is to make sure all their necessary equipment is prepared for action. I am reminded of a somewhat humorous item in the news several years ago, a photograph depicting a U.S. soldier in a combat zone who was attired in his helmet, boots, a T-shirt, flak jacket, and a pair of shorts emblazoned with "I [heart] NY". In his defense, he was off duty and had stripped down to take a nap in the shade, seeking relief from the desert heat; but when the position came under attack he put on his armor, took up his weapon, and ran to his position in the defenses. Even in a half-awake state he would not let himself become separated from his most essential pieces of equipment for fighting and survival on the battlefield. Paul tells Christians also to wake up and get our armor on:

Besides this you know the time, that the hour has come for you to wake from sleep. For salvation is nearer to us now than when we first believed. The night is far gone; the day is at hand. So then let us cast off the works of darkness and put on the armor of light (Romans 13:11-12).

Therefore take up the whole armor of God, that you may be able to withstand in the evil day, and having done all, to stand firm (Ephesians 6:13).

The saints who went before us also remind us that there is an end to this spiritual fight someday, a day we will be released from this service and called up to a more joyful purpose. The victory is guaranteed:

But thanks be to God, who gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ. Therefore, my beloved brothers, be steadfast, immovable, always abounding in the work of the Lord, knowing that in the Lord your labor is not in vain (1 Corinthians 15:57-58).

For everyone who has been born of God overcomes the world. And this is the victory that has overcome the world--our faith (1 John 5:4).

And at the end there is "the crown of life, which God has promised to those who love him" (James 1:12).

|

| Roman-era laurel. Photo by Georges Jansoone. |

The next three stanzas from How's original text are usually omitted, but add an interesting backdrop to the key ideas in the hymn:

For the Apostles’ glorious company,

Who bearing forth the Cross o’er land and sea,

Shook all the mighty world, we sing to Thee:

Alleluia, Alleluia!

For the Evangelists, by whose blest word,

Like fourfold streams, the garden of the Lord,

Is fair and fruitful, be Thy Name adored.

Alleluia, Alleluia!

For Martyrs, who with rapture kindled eye,

Saw the bright crown descending from the sky,

And seeing, grasped it, Thee we glorify.

Alleluia, Alleluia!

These have a strong similarity to the opening section of the ancient "Te Deum" prayer, even borrowing the phrasing "glorious company of the Apostles":

We praise Thee, O God; we acknowledge Thee to be the Lord.

All the earth doth worship Thee, the Father everlasting.

To Thee all Angels cry aloud, the Heavens, and all the Powers therein.

To Thee Cherubin and Seraphin continually do cry,

Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord God of Sabaoth;

Heaven and earth are full of the Majesty of Thy glory.

The glorious company of the Apostles praise Thee.

The goodly fellowship of the Prophets praise Thee.

The noble army of Martyrs praise Thee.

The holy Church throughout all the world doth acknowledge Thee;

The Father, of an infinite Majesty;

Thine honourable, true and only Son;

Also the Holy Ghost, the Comforter.

(Traditionally this was believed to be an inspired joint composition by Ambrose and Augustine on the occasion of the latter's baptism in 387 A.D., though modern scholarship has found circumstantial evidence pointing toward the 4th-century bishop Nicetas of Remesiana (Bela Palanka, Serbia). Hugh T. Henry, however, pointed out more than a century ago that there are strong parallels in a text by Cyprian of Carthage from 252 A.D. (Henry).)

How's stanza says the apostles "shook all the mighty world" with their message, perhaps referencing Haggai's prophecy of the Messiah who would shake things up: "For thus says the LORD of hosts: 'Yet once more, in a little while, I will shake the heavens and the earth and the sea and the dry land. And I will shake all nations . . ." (Haggai 2:6-7a). The Apostles continued His work so well that they also certainly "shook the world"; Paul's enemies in Thessalonica described them as "These men who have turned the world upside down" (Acts 17:6). And for this, Paul remarks to the church in Corinth,

We have become a spectacle to the world, to angels, and to men. We are fools for Christ's sake, but you are wise in Christ. We are weak, but you are strong. You are held in honor, but we in disrepute. To the present hour we hunger and thirst, we are poorly dressed and buffeted and homeless, and we labor, working with our own hands. When reviled, we bless; when persecuted, we endure; when slandered, we entreat. We have become, and are still, like the scum of the world, the refuse of all things (1 Cor 4:9b-13).

To which I can only respond in the words of the author of Hebrews, speaking of the prophets of old: "Of whom the world was not worthy!" (Hebrews 11:38). Thanks be to God for these men of courage and faith, who saw the church firmly planted across the accessible world of their day.

We can also be thankful for the four Evangelists, the writers of the gospel accounts of the life of Jesus. Matthew, the outcast from his people who yet wrote the most Jewish of all the accounts, presenting the evidence from the Hebrew Testament that Jesus is the promised Messiah; Mark, the well-traveled man of the world (and perhaps the recorder for Peter), who writes with such energy and focus that his account is still perhaps the most accessible place to start for the secular reader; Luke, the well-educated Greek physician, who recorded in clinical detail things that defied the scientific worldview of his day (and ours); and John, who contemplates the cosmic sweep of all that Christ is, interlaced with touching personal memories of the Man he knew so well. Together they give us a portrait of Christ that bursts with dimension, texture, and color.

The third stanza of this section based on the Te Deum remembers the martyrs for Christ, a subject addressed very directly in the Revelation:

When he opened the fifth seal, I saw under the altar the souls of those who had been slain for the word of God and for the witness they had borne. They cried out with a loud voice, "O Sovereign Lord, holy and true, how long before You will judge and avenge our blood on those who dwell on the earth?" Then they were each given a white robe and told to rest a little longer, until the number of their fellow servants and their brothers should be complete, who were to be killed as they themselves had been (Revelation 6:9-11).

The next stanza is omitted in Praise for the Lord, though it is usually retained in other hymnals.

O blest communion, fellowship divine!

We feebly struggle, they in glory shine;

Yet all are one in Thee, for all are Thine.

Alleluia, Alleluia!

This stanza reminds us that even in contemplation of such famous and exalted spiritual company as the apostles, evangelists, and martyrs, the ground is level at the foot of the cross; we are a fellowship of believers. Consider the numerous times that Paul, the great apostle to the Gentiles, spoke of someone as his "fellow worker" or "fellow soldier". Or hear the words of John in his first epistle: "That which we have seen and heard we proclaim also to you, so that you too may have fellowship with us; and indeed our fellowship is with the Father and with his Son Jesus Christ" (1 John 1:3). Perhaps the most dramatic instance of this equality of fellowship is demonstrated in the closing chapter of John's Revelation, when the apostle himself is struck with awe at being in the company of a mighty angel:

I, John, am the one who heard and saw these things. And when I heard and saw them, I fell down to worship at the feet of the angel who showed them to me, but he said to me, "You must not do that! I am a fellow servant with you and your brothers the prophets, and with those who keep the words of this book. Worship God" (Revelation 22:8-9).

What an encouraging thought, that even the angelic beings in God's presence invite us to stand and worship alongside them as fellow creations!

Stanza 4:

And when the strife is fierce, the warfare long,

Steals on the ear the distant triumph song,

And hearts are brave again, and arms are strong.

Alleluia, Alleluia!

The U.S. Navy has a tradition of naming the destroyer class of vessels after its heroes, and many of the names could be chapter headings in the history of that institution: John Paul Jones. Decatur. Farragut. Dewey and Gridley. Halsey and Spruance. These names are kept in remembrance in honor of those individuals, but also for the sake of those currently serving--from Jones's "I intend to go in harm's way" to Farragut's "Full speed ahead!" (preceded by a dismissive remark about torpedoes), their words and actions encapsulate the values of the service.

The writer of Hebrews gave us a similar list of heroes in the 11th chapter of that treatise, followed by the exhortation,

Therefore, since we are surrounded by so great a cloud of witnesses, let us also lay aside every weight, and sin which clings so closely, and let us run with endurance the race that is set before us, looking to Jesus, the founder and perfecter of our faith, who for the joy that was set before him endured the cross, despising the shame, and is seated at the right hand of the throne of God (Hebrews 12:1-2).

These are names worth remembering, the writer says: Abel. Enoch. Noah. Abraham and Sarah. And to these we can add the heroes, both famous and ordinary, of the New Testament; but also we can take courage from the saints we have known personally, whose examples have touched our lives directly and continue to inspire us. It is one of the "features" of middle age, I suppose, that more and more people I have loved are now gone from this life. But I remember their faces, their smiles, their words of encouragement, their patient and steady examples of Christian manhood or womanhood. I could begin listing them, but I don't know how or when I could stop. Suffice it to say, I think of one and remember his optimism and energy in spite of his loneliness in later years; I think of another and remember her gentleness and desire to see the best in people; I think of yet another and remember his humility and sweetness in a world that treated him poorly for so long. I remember them, and am ashamed of my own complaints, and am encouraged again to take up my part in the labors they carried forward so well.

The next two stanzas, depicting the current and future state of the departed saints, are omitted in Praise for the Lord.

The golden evening brightens in the west;

Soon, soon to faithful warriors comes their rest;

Sweet is the calm of paradise the blessed.

Alleluia, Alleluia!

"Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord from now on; blessed indeed, that they may rest from their labors, for their deeds follow them!" (Revelation14:13). It was with this courage and satisfaction that Paul faced his approaching death, saying "there is laid up for me the crown of righteousness, which the Lord, the righteous judge, will award to me on that day" (2 Timothy 4:8), concluding that "the Lord will rescue me from every evil deed and bring me safely into His heavenly kingdom" (2 Timothy 4:18). As the author of Hebrews argued, "there remains a Sabbath rest for the people of God, for whoever has entered God's rest has also rested from his works as God did from His" (Hebrews 4:9-10).

This is the current state of the departed saints, now in paradise awaiting the end of all things; but the next stanza begins How's depiction of the amazing climax of history, when Jesus returns in His glory.

But lo! there breaks a yet more glorious day;

The saints triumphant rise in bright array;

The King of glory passes on His way.

Alleluia, Alleluia!

The phrase "King of Glory" is found in an unusual passage that makes up the second half of the 24th Psalm:

Lift up your heads, O gates!

And be lifted up, O ancient doors,

that the King of glory may come in.Who is this King of glory?

The LORD, strong and mighty,

the LORD, mighty in battle!Lift up your heads, O gates!

And lift them up, O ancient doors,

that the King of glory may come in.Who is this King of glory?

The LORD of hosts,

He is the King of glory!

(Psalm 24:7-10)

From earth’s wide bounds, from ocean’s farthest coast,

Through gates of pearl streams in the countless host,

Singing to Father, Son and Holy Ghost:

Alleluia, Alleluia!

The final stanza captures the grand sweep of this procession, portraying the faithful from all nations and all eras in a final culmination of that promise to Abraham, "and in your offspring shall all the nations of the earth be blessed" (Genesis 22:18) and extended throughout the ages of the prophets:

I saw in the night visions, and behold, with the clouds of heaven there came one like a Son of Man, and He came to the Ancient of Days and was presented before Him. And to Him was given dominion and glory and a kingdom, that all peoples, nations, and languages should serve Him; His dominion is an everlasting dominion, which shall not pass away, and His kingdom one that shall not be destroyed (Daniel 7:13-14).

Now we see in the mind's eye that fulfillment that John saw by his vision:

After this I looked, and behold, a great multitude that no one could number, from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and languages, standing before the throne and before the Lamb, clothed in white robes, with palm branches in their hands (Rev 7:9).

May we remember the great legacy of faithfulness left to us by those saints who have gone before, and may we take courage from them to continue in the path they took, knowing that we too can be part of this glorious company.

|

| Vaughan Williams ca. 1910 |

References:

Estes, David Foster. "Saints." International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1939. https://www.internationalstandardbible.com/S/saints.html

Kittel, Gerhard, et al. Theological Dictionary of the New Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1964.

No comments:

Post a Comment